Cap Table Magic: What happens to my ownership?

Cap tables detail who owns what % of a company at a given point in time, however complexity can often arise as companies grow and new shares are issued.

This can sometimes make the answer to ‘what happens to my ownership?’ a resounding, ‘well, it depends’. Often the impacts can be non-intuitive and require detailed modelling to understand fully.

The purpose of this piece is to give a forward looking glimpse of some of the scenarios that companies may experience over time.

1. Equity financing

Let’s use a clean example and assume I have founded a company with 1,000 shares and initially I own all 1,000 shares.

QQ: If I would like to raise $1m for 10% of my business, what does the cap table look like after the transaction?

Generally in new rounds of equity financing, new preferred shares are issued which means the total number of shares in the company increases.

If we suppose the new # of shares to the investor is x, then x / (1,000 + x) needs to equal 10%. Solving, we find that x = 111 shares, which takes the total number of shares in the company up to 1,111. This means the end cap tables has me continuing to own 1,000 shares (90%), and a new investor who owns 111 (10%).

This example introduces the concept of dilution, where new investment and shares that are created ‘dilute’ one’s original ownership (in this case from 100% down to 90%) even though the number of shares I own did not change. The main reason for the creation of new shares is to do with share seniority and preferences that we will cover a little later.

While there certainly can be cases where existing shares can be sold via secondary transactions or even cancelled, these are alternate mechanisms that are exceptions to the rule — one should generally expect new shares to be issued at each equity financing event.

2. ESOP pool creation and top-up

But it isn’t just new capital that can create new shares and dilute existing ownership. Outside of new capital, another common source of intentional equity dilution comes from either the creation or topping up of an ESOP pool (employee stock ownership plan).

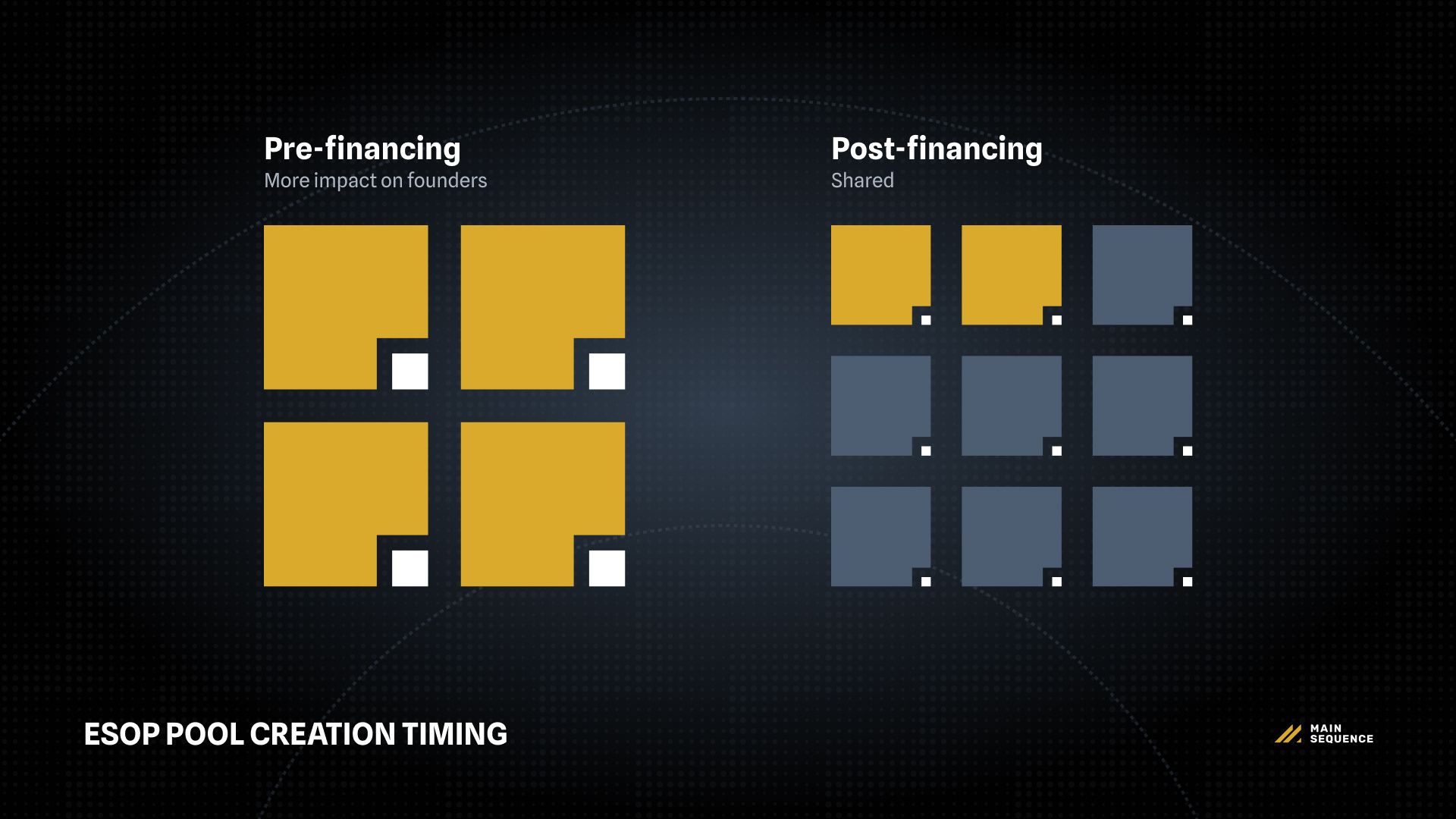

Usually as a part of equity financing rounds, new investors will want there to be a pool of shares made available for future employees. The new shares in this pool are created in the same way, diluting existing ownership as a new X% of company shares for examples, are brought into existence.

One thing to be specific about here is when these new shares are created. Given the dilutive nature of these shares, the sequencing of when the shares are created determines who gets more impacted by the dilution. For example, if the pool is created before the equity financing takes place, existing shareholders will take the entire brunt of the dilution. If the pool is created after the financing event, the dilution will be spread across both existing and new investors, which means there will be slightly less impact on existing shareholders.

While I’ve experienced both scenarios (as a new investor and as an existing investor being diluted), the norm appears to be the former, where a pool is created before the financing occurs. New investors are usually signing up to invest $ for a given % of the company, so aren’t a fan of immediately being diluted. In addition, the rationale for an ESOP is usually to enable the company to hire and incentivize key talent for their go-forward plans, so should in theory be in place before new money is raised.

If you do go down the pathway of creating/topping up a pre-round ESOP, don’t forget that given new investment will dilute existing shareholders, this will also dilute the ESOP pool itself. If you are targeting a post round pool of a certain size, the actual pool created before the round will need to be bigger to account for the dilutive impacts of the round (which can be significant in the case of say a down-round).

3. Convertible instruments (vs. Priced rounds)

While priced round equity financing events are fairly straight forward and sequential to model, what often introduces more complexity is convertible instruments. Both SAFE and convertible notes are debt instruments that convert to equity at some point in the future, so this is where modelling what one’s cap table might look like can become trickier.

In general, the way that convertible instruments work is that some $ invested converts to equity at the next priced round. The conversion price for this equity is usually (there can be other mechanisms also) the lower of the next round price with a % discount and/or a valuation cap on a pre-note or post-note basis (i.e. before or after the note money). The main takeaway here is that the ownership these notes will convert into completely depends on the terms of a future round, and could vary wildly depending on the performance of the company.

While this makes for fun scenario modelling, it can make it difficult to definitively predict what happens to existing shareholders’ ownership. As such, it’s important when thinking about accepting convertible instruments to model out a range of upside and downside scenarios so that one can get a sense of the impact on ownership. One could write an entire series of posts on the nuances of convertible instruments, but for now just know that they can add some complexity to your cap table management, to which I would prescribe a healthy amount of scenario modelling.

So why would one ever consider a convertible instrument over a priced round? The main advantage is that the overall process is much faster than a priced round, which can be important for getting cash into a business. While some also say that not having to lock in a valuation for the business is also a benefit, in practice there is often a similar level of discussion around the discount + valuation caps, that are in essence trying to value the business at that point in time.

4. Antidilution provisions

A final mechanism to call out is antidilution, which is designed to protect preference shareholders, usually investors, in the event of a down-round i.e. where the new PPS, price per share, is lower than what was paid by a previous investor. If a down-round is to occur, those with antidilution rights (usually investors with preference shares) are issued additional shares to make up for the down-round shortfall, and the amount issued depends on what antidilution mechanism was agreed to.

Without going into too much detail, there are generally three antidilution mechanisms. These are: broad based weighted average, narrow based weighted average, and full ratchet — each of these has a different calculation basis for the number of antidilution shares issued, and in most cases these shares are issued post round after completion so there is some dilutive impact for new investors. The extent of this however is dependent on how much lower the new PPS is compared to previous rounds, and note that each existing preference shareholder will get a different amount of antidilution shares depending on their original entry PPS and how much they invested.

If you’re a Founder reading this, I truly hope that you never need to think about antidilution at all and it forever sits as a dormant provision in the background. Sadly, the occasions where antidilution does kick in are almost always painful, and usually come with a complex array of other things all happening at the same time.

5. Putting it all together

While each of the above mechanisms are fairly straight forward alone, when they happen together is when things get really tricky.

Imagine a situation where a company is thinking about raising a priced down-round, into which multiple note instruments are converting (each with different discounts and valuation caps), which also needs a significant ESOP pool top-up, after which antidilution shares also need to be issued to previous investors.

So what happens to my ownership again?

This is where the answer isn’t obvious, and you will want to do some careful modelling to fully articulate the impact on all shareholders new and existing.

If you’re thinking through any interesting or unique scenarios, please reach out and we’d be happy to see what we can do to help!

Written by

Stay in Touch

.jpg)